Cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine that is caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. The main symptoms are profuse watery diarrhea and vomiting. Transmission is primarily through consuming contaminated drinking water or food. The severity of the diarrhea and vomiting can lead to rapid dehydration and electrolyte imbalance. Primary treatment is with oral rehydration solution and if these are not tolerated, intravenous fluids. Antibiotics are beneficial in those with severe disease. Worldwide it affects 3-5 million people and causes 100,000-130,000 deaths a year as of 2010. Cholera was one of the earliest infections to be studied by epidemiologicalmethods.[citation needed]

Contents |

[edit]Signs and symptoms

The primary symptoms of cholera are profuse painless diarrhea and vomiting of clear fluid.[1] These symptoms usually start suddenly, one to five days after ingestion of the bacteria.[1] The diarrhea is frequently described as "rice water" in nature and may have a fishy odor.[1] An untreated person with cholera may produce 10-20 liters of diarrhea a day[1] with fatal results. For every symptomatic person there are 3 to 100 people who get the infection but remain asymptomatic.[2]

If the severe diarrhea and vomiting are not aggressively treated it can, within hours, result in life-threatening dehydration and electrolyte imbalances.[1] The typical symptoms of dehydration include low blood pressure, poor skin turgor (wrinkled hands), sunken eyes, and a rapid pulse.[1]

[edit]Cause

Main article: Vibrio cholerae

Transmission is primarily due to the fecal contamination of food and water due to poorsanitation.[3] This bacterium can, however, live naturally in any environment.[4]

[edit]Susceptibility

About one hundred million bacteria must typically be ingested to cause cholera in a normal healthy adult.[1] This dose, however, is less in those with lower gastric acidity (for instance those using proton pump inhibitors).[1] Children are also more susceptible with two to four year olds having the highest rates of infection.[1] Individuals' susceptibility to cholera is also affected by theirblood type, with those with type O blood being the most susceptible.[1][5]

It has been said that cystic fibrosis genetic mutation in humans has maintained a selective advantage: heterozygous carriers of the mutation (who are thus not affected by cystic fibrosis) are more resistant to V. cholerae infections.[6] In this model, the genetic deficiency in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator channel proteins interferes with bacteria binding to the gastrointestinal epithelium, thus reducing the effects of an infection.

[edit]Transmission

Cholera is typically transmitted by either contaminated food or water. In the developed world, seafood is the usual cause, while in the developing world it is more often water.[1] Cholera has been found in only two other animal populations: shellfish and plankton.[1]

People infected with cholera often have diarrhea, and if this highly liquid stool, colloquially referred to as "rice-water," contaminates water used by others, disease transmission may occur.[7] The source of the contamination is typically other cholera sufferers when their untreated diarrheal discharge is allowed to get into waterways or into groundwater or drinking water supplies. Drinking any infected water and eating any foods washed in the water, as well as shellfish living in the affected waterway, can cause a person to contract an infection. Cholera is rarely spread directly from person to person. Both toxic and nontoxic strains exist. Nontoxic strains can acquire toxicity through a temperate bacteriophage.[8] Coastal cholera outbreaks typically followzooplankton blooms, thus making cholera a zoonotic disease.

[edit]Mechanism

Most bacteria, when consumed, do not survive the acidic conditions of the human stomach.[9] The few bacteria that do survive conserve theirenergy and stored nutrients during the passage through the stomach by shutting down much protein production. When the surviving bacteria exit the stomach and reach the small intestine, they need to propel themselves through the thick mucus that lines the small intestine to get to the intestinal walls, where they can thrive. V. cholerae bacteria start up production of the hollow cylindrical protein flagellin to make flagella, the cork-screw helical fibers they rotate to propel themselves through the mucus of the small intestine.

Once the cholera bacteria reach the intestinal wall, they no longer need the flagella propellers to move. The bacteria stop producing the protein flagellin, thus again conserving energy and nutrients by changing the mix of proteins which they manufacture in response to the changed chemical surroundings. On reaching the intestinal wall, V. cholerae start producing the toxic proteins that give the infected person a watery diarrhea. This carries the multiplying new generations of V. cholerae bacteria out into the drinking water of the next host if proper sanitation measures are not in place.

The cholera toxin (CTX or CT) is an oligomeric complex made up of six protein subunits: a single copy of the A subunit (part A), and five copies of the B subunit (part B), connected by a disulfide bond. The five B subunits form a five-membered ring that binds to GM1 gangliosideson the surface of the intestinal epithelium cells. The A1 portion of the A subunit is an enzyme that ADP-ribosylates G proteins, while the A2 chain fits into the central pore of the B subunit ring. Upon binding, the complex is taken into the cell via receptor-mediated endocytosis. Once inside the cell, the disulfide bond is reduced, and the A1 subunit is freed to bind with a human partner protein called ADP-ribosylation factor 6(Arf6).[10] Binding exposes its active site, allowing it to permanently ribosylate the Gs alpha subunit of the heterotrimeric G protein. This results in constitutive cAMP production, which in turn leads to secretion of H2O, Na+, K+, Cl−, and HCO3− into the lumen of the small intestine and rapid dehydration. The gene encoding the cholera toxin is introduced into V. cholerae by horizontal gene transfer. Virulent strains of V. cholerae carry a variant of temperate bacteriophage called CTXf or CTXφ.

Microbiologists have studied the genetic mechanisms by which the V. cholerae bacteria turn off the production of some proteins and turn on the production of other proteins as they respond to the series of chemical environments they encounter, passing through the stomach, through the mucous layer of the small intestine, and on to the intestinal wall.[11] Of particular interest have been the genetic mechanisms by which cholera bacteria turn on the protein production of the toxins that interact with host cell mechanisms to pump chloride ions into the small intestine, creating an ionic pressure which prevents sodium ions from entering the cell. The chloride and sodium ions create a salt-water environment in the small intestines, which through osmosis can pull up to six liters of water per day through the intestinal cells, creating the massive amounts of diarrhea. The host can become rapidly dehydrated if an appropriate mixture of dilute salt water and sugar is not taken to replace the blood's water and salts lost in the diarrhea.

By inserting separate, successive sections of V. cholerae DNA into the DNA of other bacteria, such as E. coli that would not naturally produce the protein toxins, researchers have investigated the mechanisms by which V. cholerae responds to the changing chemical environments of the stomach, mucous layers, and intestinal wall. Researchers have discovered there is a complex cascade of regulatory proteins that control expression of V. cholerae virulence determinants. In responding to the chemical environment at the intestinal wall, the V. cholerae bacteria produce the TcpP/TcpH proteins, which, together with the ToxR/ToxS proteins, activate the expression of the ToxT regulatory protein. ToxT then directly activates expression of virulence genes that produce the toxins, causing diarrhea in the infected person and allowing the bacteria to colonize the intestine.[11] Current research aims at discovering "the signal that makes the cholera bacteria stop swimming and start to colonize (that is, adhere to the cells of) the small intestine."[11]

[edit]Genetic structure

Amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) fingerprinting of the pandemic isolates of Vibrio cholerae has revealed variation in the genetic structure. Two clusters have been identified: Cluster I and Cluster II. For the most part, Cluster I consists of strains from the 1960s and 1970s, while Cluster II largely contains strains from the 1980s and 1990s, based on the change in the clone structure. This grouping of strains is best seen in the strains from the African continent.[12]

[edit]Diagnosis

A rapid dip-stick test is available to determine the presence of V. cholerae.[4] In those that test positive, further testing should be done to determine antibiotic resistance.[4] In epidemic situations, a clinical diagnosis may be made by taking a history and doing a brief examination. Treatment is usually started without or before confirmation by laboratory analysis.

Stool and swab samples collected in the acute stage of the disease, before antibiotics have been administered, are the most useful specimens for laboratory diagnosis. If an epidemic of cholera is suspected, the most common causative agent is Vibrio cholerae O1. If V. cholerae serogroup O1 is not isolated, the laboratory should test for V. cholerae O139. However, if neither of these organisms is isolated, it is necessary to send stool specimens to a reference laboratory. Infection with V. cholerae O139 should be reported and handled in the same manner as that caused by V. cholerae O1. The associated diarrheal illness should be referred to as cholera and must be reported in the United States.[13]

A number of special media have been employed for the cultivation for cholera vibrios. They are classified as follows:

[edit]Enrichment media

- Alkaline peptone water at pH 8.6

- Monsur's taurocholate tellurite peptone water at pH 9.2

[edit]Plating media

- Alkaline bile salt agar (BSA): The colonies are very similar to those on nutrient agar.

- Monsur's gelatin Tauro cholate trypticase tellurite agar (GTTA) medium: Cholera vibrios produce small translucent colonies with a greyish black center.

- TCBS medium: This the mostly widely used medium; it contains thiosulphate, citrate, bile salts and sucrose. Cholera vibrios produce flat 2–3 mm in diameter, yellow nucleated colonies.

Direct microscopy of stool is not recommended, as it is unreliable. Microscopy is preferred only after enrichment, as this process reveals the characteristic motility of Vibrio and its inhibition by appropriate antisera. Diagnosis can be confirmed, as well, as serotyping done byagglutination with specific sera.

[edit]Prevention

Although cholera may be life-threatening, prevention of the disease is normally straightforward if proper sanitation practices are followed. In developed countries, due to nearly universal advancedwater treatment and sanitation practices, cholera is no longer a major health threat. The last major outbreak of cholera in the United States occurred in 1910-1911.[14][15] Effective sanitation practices, if instituted and adhered to in time, are usually sufficient to stop an epidemic. There are several points along the cholera transmission path at which its spread may be halted:

- Sterilization: Proper disposal and treatment of infected fecal waste water produced by cholera victims and all contaminated materials (e.g. clothing, bedding, etc.) is essential. All materials that come in contact with cholera patients should be sterilized by washing in hot water, usingchlorine bleach if possible. Hands that touch cholera patients or their clothing, bedding, etc., should be thoroughly cleaned and disinfected with chlorinated water or other effective antimicrobial agents.

- Sewage: antibacterial treatment of general sewage by chlorine, ozone, ultraviolet light or other effective treatment before it enters the waterways or underground water supplies helps prevent undiagnosed patients from inadvertently spreading the disease.

- Sources: Warnings about possible cholera contamination should be posted around contaminated water sources with directions on how to decontaminate the water (boiling, chlorination etc.) for possible use.

- Water purification: All water used for drinking, washing, or cooking should be sterilized by either boiling, chlorination, ozone water treatment, ultraviolet light sterilization (e.g. by solar water disinfection), or antimicrobial filtration in any area where cholera may be present. Chlorination and boiling are often the least expensive and most effective means of halting transmission. Cloth filters, though very basic, have significantly reduced the occurrence of cholera when used in poor villages inBangladesh that rely on untreated surface water. Better antimicrobial filters, like those present in advanced individual water treatment hiking kits, are most effective. Public health education and adherence to appropriate sanitation practices are of primary importance to help prevent and control transmission of cholera and other diseases.

[edit]Surveillance

Surveillance and prompt reporting allow for containing cholera epidemics rapidly. Cholera exists as a seasonal disease in many endemic countries, occurring annually mostly during rainy seasons. Surveillance systems can provide early alerts to outbreaks, therefore leading to coordinated response and assist in preparation of preparedness plans. Efficient surveillance systems can also improve the risk assessment for potential cholera outbreaks. Understanding the seasonality and location of outbreaks provide guidance for improving cholera control activities for the most vulnerable.[16] For prevention to be effective it is important that cases are reported to national health authorities.[1]

[edit]Vaccine

A number of safe and effective oral vaccines for cholera are available.[3][17] Dukoral, an orally administered, inactivated whole cell vaccine, has an efficacy of 85%, with minimal side effects.[18] It is available in over 60 countries. However, it is not currently recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for most people traveling from the United States to the third world.[19] One injectable vaccine was found to be effective for two to three years. It must be noted that the protective efficacy was 28% lower in children less than 5 years old.[17]However, as of 2010, it has limited availability.[3] Work is under way to investigate the role of mass vaccination.[20] The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends immunization of high risk groups, such as children and people with HIV, in countries where this disease isendemic.[3] If people are immunized broadly, herd immunity results, with a decrease in the amount of contamination in the environment.[4]

[edit]Treatment

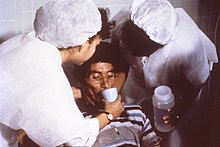

[edit]Fluids

In most cases, cholera can be successfully treated with oral rehydration therapy (ORT),which is highly effective, safe, and simple to administer.[4] Rice-based solutions are preferred to glucose-based ones due to greater efficiency.[4] In severe cases with significant dehydration, intravenousrehydration may be necessary. Ringer's lactate is the preferred solution.[1] Large volumes and continued replacement until diarrhea has subsided may be needed.[1] Ten percent of a person's body weight in fluid may need to be given in the first two to four hours.[1] This method was first tried on a mass scale during a war in Pakistan, and was found to have much success.[21]

If commercially produced oral rehydration solutions are too expensive or difficult to obtain, solutions can be made. One such recipe calls for 1 liter of boiled water, 1 teaspoon of salt, 8 teaspoons of sugar, and added mashed banana for potassium and to improve taste.[22]

[edit]Electrolytes

As there frequently is initially acidosis, the potassium level may be normal, even though large losses have occurred.[1] As the dehydration is corrected, potassium levels may decrease rapidly, and thus need to be replaced.[1]

[edit]Antibiotics

Antibiotic treatments for one to three days shorten the course of the disease and reduce the severity of the symptoms.[1] People will recover without them, however, if sufficient hydration is maintained.[4] Doxycycline is typically used first line, although some strains of V. choleraehave shown resistance.[1] Testing for resistance during an outbreak can help determine appropriate future choices.[1] Other antibiotics that have been proven effective include cotrimoxazole, erythromycin, tetracycline, chloramphenicol, and furazolidone.[23] Fluoroquinolones, such as norfloxacin, also may be used, but resistance has been reported.[24]

In many areas of the world, antibiotic resistance is increasing. In Bangladesh, for example, most cases are resistant to tetracycline,trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and erythromycin.[4] Rapid diagnostic assay methods are available for the identification of multiple drug-resistant cases.[25] New generation antimicrobials have been discovered which are effective against in in vitro studies.[26]

[edit]Prognosis

If people with cholera are treated quickly and properly, the mortality rate is less than 1%; however, with untreated cholera, the mortality rate rises to 50–60%.[1][27] For certain genetic strains of cholera, such as the one present during the 2010 epidemic in Haiti and the 2004 outbreak in India, death can occur within two hours of the first sign of symptoms.[28]

[edit]Epidemiology

See also: Cholera outbreaks and pandemics

It is estimated that cholera affects 3-5 million people worldwide, and causes 100,000-130,000 deaths a year as of 2010.[3] This occurs mainly in the developing world.[29] In the early 1980s, death rates are believed to have been greater than 3 million a year.[1] It is difficult to calculate exact numbers of cases, as many go unreported due to concerns that an outbreak may have a negative impact on the tourism of a country.[4] Cholera remains both epidemic and endemic in many areas of the world.[1]

Although much is known about the mechanisms behind the spread of cholera, this has not led to a full understanding of what makes cholera outbreaks happen some places and not others. Lack of treatment of human feces and lack of treatment of drinking water greatly facilitate its spread, but bodies of water can serve as a reservoir, and seafood shipped long distances can spread the disease. Cholera was not known in the Americas for most of the 20th century, but it reappeared towards the end of that century and seems likely to persist.[30]

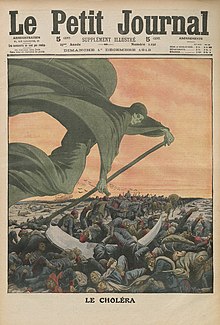

[edit]History

The word cholera is from Greek: χολέρα kholera from χολή kholē "bile". Cholera likely has its origins in the Indian subcontinent; it has been prevalent in the Ganges delta since ancient times.[1] The disease first spread by trade routes (land and sea) to Russia in 1817, then toWestern Europe, and from Europe to

Comments

Post a Comment